It can’t get no worse

Blood thundering, echoing through my ears. Sweat pouring off my face. Heaving, rasping breaths.

And we’ve only been climbing this “mountain” for 10 minutes.

I reason with myself. Everyone else seems to be fine. I can’t need a break. If I ask to stop, everyone will know how out of shape I am.

I chug down more sun-boiled water.

Rose: Shall we take a moment?

Naomi: [Be cool. Be cool.] Oh dear God, yes. I think I’m dying.

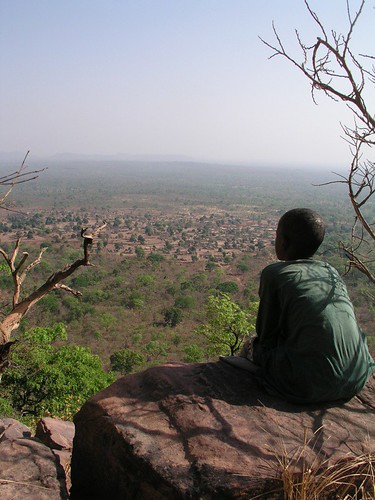

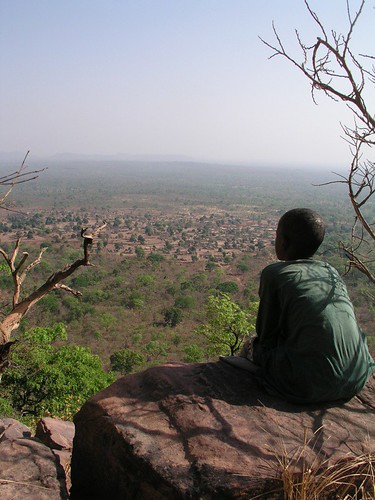

We stop, and our entourage of ten-year-old guides waits patiently for us to recover. It’s not yet 9 am, and the heat is already breaking us. It’s our second day in Dindafalou, and we’re heading up one of the nearby mountains to see some caves and the source of the waterfall. We’d heard about the hike from our new friend Ricard (his nickname), who we’d picked up in the village the night before.

Naomi and Rose: What do people do in Dindafalou on a Saturday night?

Ricard: Dindafalou? This village on the Guinean border? In the middle of the bush? With no electricity? Or roads?

Naomi and Rose: Right. That’s the one. Where’re are the cool kids hanging out tonight?

Ricard: [Oh lord. How do I always get stuck with these crazy white people?] Well… You should probably just hope that someone invites you to their house. [Damn. Now it’s hanging out there. Stupid Senegalese hospitality.] Soooo… would you like to come over for Senegalese tea tonight?

Naomi and Rose: Yeah, sounds great!

Ricard, who also worked at our campement, turned out to be a font of knowledge and suggestions. Not unlike most of the other people we met along our way, who also had plenty of ideas of where we should go, and how we should get there. But Ricard’s information was different, in that it was all true.

To wit:

Rose’s taxi driver in Dakar: You’re going to Mali! That’s where I’m from! The road there is fantastic, and there are cars that go all the time!

Road to Mali: He’s lying. I don’t exist.

Everyone we asked besides Ricard: The market in Dindafalou starts first thing in the morning, by about 8 am.

Ricard: It doesn’t get going until around 1 pm, when all the out of town vendors arrive.

Market at 8 am: What? You’re here? No, I’m up, I’m up. I swear, I wasn’t sleeping. I’m just… Can you come back in a few hours?

And thus we found ourselves following his suggestion of hiking up the mountain in the morning, before it got “too hot.”

We’d picked up our guides in our usual way. We started walking (in the wrong) direction, and stopped the first friendly face we saw to ask.

Naomi: Which way do we go to get up the mountain?

Little boy: [Points back the way we came, in the direction of the rocky mountain.]

Naomi: Right. So… That way?

Little boy: [Nods]

Naomi: You wanna come with?

Little me: You want me to come with you?

Naomi: You know… if you want to….

Little boy: [shrug]

And then two of his friends materialized to keep him company, and we were off. And up.

I guess I expected a hill. You know, maybe a bit steep in parts. With a few good spots to enjoy the pretty view.

What we got was essentially vertical rock climbing. Any steeper and we’d have needed crampons. During our second break, I asked an ill-advised question: Is this the same hill you climb to get to Guinea?

Because, after talking the night before to Ricard, we’d determined that we’d probably be walking to Guinea. We’d always considered it a possibility, and despite the unexpected presence of real mountains and the soul-melting heat, we still thought we could handle 30 km in a single day. Word was, you climbed the first hill, had a long, flat walk, and then climbed a second hill right before the end. Seemed doable.

Little kid: No, you don’t have to climb this hill to get to Guinea.

Naomi: Phew!

Little kid: You climb that one [points]. It’s bigger.

At this point, I began to doubt our walking to Guinea plan. How would I survive a hill bigger and steeper than this one, while carrying my backpack, and my share of the many liters of water we’d need?

I silenced my doubts (though not my pounding pulse or hacking gasps for air) and kept climbing.

****

Rose: So we’ll just ask around the market. Someone’s got to have a car or truck and be driving back towards Mali.

Naomi: Absolutely. And that way, we’ll probably get there tonight, and have a whole extra day in Guinea.

Rose: It’s not that we couldn’t have walked.

Naomi: Oh, we totally could have.

Rose: It’s just that it’s so hot. And carrying all that water!

Naomi: We’re still totally hardcore.

Rose: The hardest.

****

Naomi: So….

Rose: What if we bribe the Senegalese border guard to just give you a new stamp in your passport?

Naomi: The blind one?

Rose: Yeah. He won’t care. And then we’ll go to the National Park near Kedougou, and who cares that we didn’t *actually* leave the country.

Naomi: Right. What were we going to do in Guinea anyway?

Rose: Plus, we can always tell everyone we were there. What do they know?

****

It was hot. Really hot. There were cars going to Kedougou. But nothing going to Mali. There were rumors that cars might possibly go to Mali from nearby Segou. We might just have to wait a few days until one passed. Or a week.

We’d had lunch (bread, avocado, mango) and cooled off with a drink of refreshingly tepid bottled water (ahhh!), and it was decision time.

Were we going to go backwards? Back to Kedougou (and the amazing steak frites dinner)? Or were we going to brave forward? Cross the frontier?

Suddenly Ricard—friendly, knowledgeable, bald, Ricard—appeared at our side.

“How’s it going?”

We spilled our fears, our hopes, our dreams of reaching Mali, and the obstacles in our way. Could we make it to Guinea? Would someone carry our stuff?

And Ricard, a man of few words, but who made them count, took charge. We would spend the night at his house, and leave at 4 am with Muxtar, our newly-hired guide. There would be a bicycle waiting at the top of the first mountain, and Muxtar would use that to carry our backpacks and water across the 30+ km. We’d buy bread and sardines and 15 litres of water and spend the hottest part of the afternoon in a village at the base of the final mountain (if we were good walkers). We could be in Mali by 10 pm or earlier. If we walked slowly, we’d spend the night in the village, and climb the mountain the following morning.

Rose: Okay, sure, the mountain was tough this morning. But we didn’t ACTUALLY have heart attacks.

Naomi: And it was over in 45 minutes. Plus, it’ll still be dark at 4 am, so it won’t be so hot.

Rose: The flat part won’t be a problem at all. So just two little mountains at the beginning and end.

Naomi: We can so do this. .

Rose: Totally.

And that, my friends, THAT is how I ended up climbing up the rocky face of a small mountain in the pre-dawn, our path lit by the moon and Rose and my headlamps. And though the brutal heat of the sun was hours away, it was already hot and humid, and I was already covered in a greasy layer of sweat.

And here’s where I’ll finally get back to my original point, which is that, if I had never run a marathon, I would never have believed that I could climb two mountains and walk 30 or so kilometers. I wouldn’t have entertained the possibility, and I would have found some other way to leave the country. But post-marathon-Naomi? Scoffs at physical pain. 30 kilometers? Is that all, she says?

You know what? Despite those niggling early morning doubts, the truth is that 2 little mountains and 30 km really is entirely doable. What I didn’t know then was that Ricard, reliable, informative, Ricard, had employed a wee bit of… understatement.

The first “mountain” was small. The second was… well, to be blunt, enormous. Our first clue came when the sun rose, and Muxtar pointed to the giant mountain range looming far ahead.

Muxtar: That’s the mountain we need to climb to get to Guinea.

Rose: He’s joking.

Naomi: I don’t know why you think that.

Rose: Ricard said nothing about such a big mountain. Ricard never lies.

Naomi: Oh…. Kay.

On we marched toward the mountain that loomed ever larger with each step.

Muxtar: Actually, we have to climb 3 mountains.

Rose: That’s not true.

Naomi: Why would he lie?

Rose: Why would my taxi driver tell me there were cars to Mali? Everybody lies.

Naomi: So… Right.

It turned out that Muxtar wasn’t telling the truth about there being three mountains to climb.

There were four.

And when he told us later that we’d have to walk a bit farther from the peak to arrive at Mali, that wasn’t true either.

It was two hours of scrambling into and out of dry riverbeds, up steep hills (the kind I thought passed for “mountains” in West Africa, until I was confronted with the real thing), downhill for a moment, and then up even more steep hills.

As Rose began to question whether Mali even existed, I began to argue with Muxtar about the remaining hills.

“We only need to go up, and then down, and then up, and then down, and then up one final time,” he reassured me.

“But you said that half an hour ago, and we’ve already gone up and down twice since then. So this has to be the last hill.” I reasoned, very logically, and not at all petulantly, as if I could argue away the existence of the three hills that remained between us and our destination. It was nearly 10 pm. Muxtar, who was still carrying all our stuff, just smiled patiently, and said, “It’s not far. We’re almost there.”

****

This is an awful lot of whining for what was, in reality, a beautiful hike. We passed through tiny villages, and admired the sunrise (and the sunset). We stopped in one village and offered a man 40 cents for some mangoes from his tree. He started picking, and before we understood what was happening, Muxtar was piling more than twenty mangoes into the already outlandish load he was leading on his bicycle.

We spent a couple hours resting (in a sweaty, sore, heap) in a village at the base of a mountain, where they shared their lunch and their tea, and cheerfully wished us well on the rest of our journey.

And, at first as a distraction against fatigue and the heat, and later because it was so entertaining, (and as a distraction against the exhaustion and pain) Rose and I told each other story after story from our lives and those of our friends.

Rose: Everything you’ve ever heard about boarding school is true…

Naomi: … just as she was about to get deported…

And when we finally arrived in Mali near 10 pm, a mere 18 hours after we’d left Dindafalou, we were tired. We were upset that people had so understated the mountain and the subsequent 10 km. But we weren’t broken.

Yet.

****

Random boy from village: Hello! [Knock, knock, knock] Grand! Hello!

Naomi: HELLOOOOO! [BANG, BANG, BANG.] HEEEEEEELLLLLLLLLOOOOOOO!!??

Rose: There’s nobody there.

Muxtar: There’s nobody there.

Naomi: [BANG. BANG. BANG] HELLLLLOOOOOOOO!!!!!!!

We knew of one hotel in the village of Mali. It was called the Auberge Indigo, and a Peace Corps volunteer we’d met in the village before climbing the last mountain had told us about it.

It’s right by the entrance to the village, she’d assured us.

Of course, she’d also told us that from the peak of the mountain, it’d be an hour’s flat walk to Mali. Everybody lies.

When we finally arrived in the village, we asked for help finding the hotel. 30 minutes of (hilly) walking later, we’d finally arrived at the Auberge. There was a light on inside, but the gate was locked.

Muxtar: There’s nobody there.

Naomi: [BANG. SOB. BANG.] Hello?

Rose: Where else can we stay tonight?

Muxtar: I know a place.

It was a block or so from where we’d been when we arrived and asked for directions to the Auberge. It was also pitch black and deserted.

Rose: And here I was wondering how tonight could get worse.

Muxtar: There’s nobody there.

Rose: Where else can we stay tonight?

Muxtar: I know a place.

We started walking again. It was now after 11 pm.

Rose: All I want is a bed and a place where I can wash off all this sweat.

Naomi: I caution you against getting your hopes up.

And here is where deliverance appeared, in the form of two boys on a motorcycle. They stopped to talk to Muxtar.

Rose: I’m going to ask them for a place to stay.

She meant at their house. Amazingly, however, there was a guesthouse. A weird, almost complete hotel/apartment/villa with tiled, fitted bathrooms, (including large tubs and bidets, in a place with no running water) and built-in light fixtures (in a place with no electricity). There was also a giant, king size bed, with a real, toubab mattress. And while Rose broke down in the bathroom, I settled the details with our well-meaning, but slightly clueless hosts, who wanted to know if we’d be ready to go sightseeing at 7 in the morning, and if maybe we wanted to look at the other rooms before deciding which one to sleep in. (Rose: JUST LEAVE! NOW!)

And we finally settled into bed, hysterically, desperately laughing at our exhaustion, at the employee from the Auberge Indigo who had chased us down right before we found our new hotel, and who wanted us to follow him 45 minutes in the OTHER direction back to his hotel (“But I’m here now! I went out to get some bread! But I’m here!”) and at how much we wished we were back home in Senegal.

But then I stopped laughing. “We can’t just leave here and go back to Senegal tomorrow,” I told Rose. “We have to stay here, and we have to have fun. This trip can’t just be about having an awful time. We’ve come so far to get here. Things have to get better now.”

To be continued…

And we’ve only been climbing this “mountain” for 10 minutes.

I reason with myself. Everyone else seems to be fine. I can’t need a break. If I ask to stop, everyone will know how out of shape I am.

I chug down more sun-boiled water.

Rose: Shall we take a moment?

Naomi: [Be cool. Be cool.] Oh dear God, yes. I think I’m dying.

We stop, and our entourage of ten-year-old guides waits patiently for us to recover. It’s not yet 9 am, and the heat is already breaking us. It’s our second day in Dindafalou, and we’re heading up one of the nearby mountains to see some caves and the source of the waterfall. We’d heard about the hike from our new friend Ricard (his nickname), who we’d picked up in the village the night before.

Naomi and Rose: What do people do in Dindafalou on a Saturday night?

Ricard: Dindafalou? This village on the Guinean border? In the middle of the bush? With no electricity? Or roads?

Naomi and Rose: Right. That’s the one. Where’re are the cool kids hanging out tonight?

Ricard: [Oh lord. How do I always get stuck with these crazy white people?] Well… You should probably just hope that someone invites you to their house. [Damn. Now it’s hanging out there. Stupid Senegalese hospitality.] Soooo… would you like to come over for Senegalese tea tonight?

Naomi and Rose: Yeah, sounds great!

Ricard, who also worked at our campement, turned out to be a font of knowledge and suggestions. Not unlike most of the other people we met along our way, who also had plenty of ideas of where we should go, and how we should get there. But Ricard’s information was different, in that it was all true.

To wit:

Rose’s taxi driver in Dakar: You’re going to Mali! That’s where I’m from! The road there is fantastic, and there are cars that go all the time!

Road to Mali: He’s lying. I don’t exist.

Everyone we asked besides Ricard: The market in Dindafalou starts first thing in the morning, by about 8 am.

Ricard: It doesn’t get going until around 1 pm, when all the out of town vendors arrive.

Market at 8 am: What? You’re here? No, I’m up, I’m up. I swear, I wasn’t sleeping. I’m just… Can you come back in a few hours?

And thus we found ourselves following his suggestion of hiking up the mountain in the morning, before it got “too hot.”

We’d picked up our guides in our usual way. We started walking (in the wrong) direction, and stopped the first friendly face we saw to ask.

Naomi: Which way do we go to get up the mountain?

Little boy: [Points back the way we came, in the direction of the rocky mountain.]

Naomi: Right. So… That way?

Little boy: [Nods]

Naomi: You wanna come with?

Little me: You want me to come with you?

Naomi: You know… if you want to….

Little boy: [shrug]

And then two of his friends materialized to keep him company, and we were off. And up.

I guess I expected a hill. You know, maybe a bit steep in parts. With a few good spots to enjoy the pretty view.

What we got was essentially vertical rock climbing. Any steeper and we’d have needed crampons. During our second break, I asked an ill-advised question: Is this the same hill you climb to get to Guinea?

Because, after talking the night before to Ricard, we’d determined that we’d probably be walking to Guinea. We’d always considered it a possibility, and despite the unexpected presence of real mountains and the soul-melting heat, we still thought we could handle 30 km in a single day. Word was, you climbed the first hill, had a long, flat walk, and then climbed a second hill right before the end. Seemed doable.

Little kid: No, you don’t have to climb this hill to get to Guinea.

Naomi: Phew!

Little kid: You climb that one [points]. It’s bigger.

At this point, I began to doubt our walking to Guinea plan. How would I survive a hill bigger and steeper than this one, while carrying my backpack, and my share of the many liters of water we’d need?

I silenced my doubts (though not my pounding pulse or hacking gasps for air) and kept climbing.

****

Rose: So we’ll just ask around the market. Someone’s got to have a car or truck and be driving back towards Mali.

Naomi: Absolutely. And that way, we’ll probably get there tonight, and have a whole extra day in Guinea.

Rose: It’s not that we couldn’t have walked.

Naomi: Oh, we totally could have.

Rose: It’s just that it’s so hot. And carrying all that water!

Naomi: We’re still totally hardcore.

Rose: The hardest.

****

Naomi: So….

Rose: What if we bribe the Senegalese border guard to just give you a new stamp in your passport?

Naomi: The blind one?

Rose: Yeah. He won’t care. And then we’ll go to the National Park near Kedougou, and who cares that we didn’t *actually* leave the country.

Naomi: Right. What were we going to do in Guinea anyway?

Rose: Plus, we can always tell everyone we were there. What do they know?

****

It was hot. Really hot. There were cars going to Kedougou. But nothing going to Mali. There were rumors that cars might possibly go to Mali from nearby Segou. We might just have to wait a few days until one passed. Or a week.

We’d had lunch (bread, avocado, mango) and cooled off with a drink of refreshingly tepid bottled water (ahhh!), and it was decision time.

Were we going to go backwards? Back to Kedougou (and the amazing steak frites dinner)? Or were we going to brave forward? Cross the frontier?

Suddenly Ricard—friendly, knowledgeable, bald, Ricard—appeared at our side.

“How’s it going?”

We spilled our fears, our hopes, our dreams of reaching Mali, and the obstacles in our way. Could we make it to Guinea? Would someone carry our stuff?

And Ricard, a man of few words, but who made them count, took charge. We would spend the night at his house, and leave at 4 am with Muxtar, our newly-hired guide. There would be a bicycle waiting at the top of the first mountain, and Muxtar would use that to carry our backpacks and water across the 30+ km. We’d buy bread and sardines and 15 litres of water and spend the hottest part of the afternoon in a village at the base of the final mountain (if we were good walkers). We could be in Mali by 10 pm or earlier. If we walked slowly, we’d spend the night in the village, and climb the mountain the following morning.

Rose: Okay, sure, the mountain was tough this morning. But we didn’t ACTUALLY have heart attacks.

Naomi: And it was over in 45 minutes. Plus, it’ll still be dark at 4 am, so it won’t be so hot.

Rose: The flat part won’t be a problem at all. So just two little mountains at the beginning and end.

Naomi: We can so do this. .

Rose: Totally.

And that, my friends, THAT is how I ended up climbing up the rocky face of a small mountain in the pre-dawn, our path lit by the moon and Rose and my headlamps. And though the brutal heat of the sun was hours away, it was already hot and humid, and I was already covered in a greasy layer of sweat.

And here’s where I’ll finally get back to my original point, which is that, if I had never run a marathon, I would never have believed that I could climb two mountains and walk 30 or so kilometers. I wouldn’t have entertained the possibility, and I would have found some other way to leave the country. But post-marathon-Naomi? Scoffs at physical pain. 30 kilometers? Is that all, she says?

You know what? Despite those niggling early morning doubts, the truth is that 2 little mountains and 30 km really is entirely doable. What I didn’t know then was that Ricard, reliable, informative, Ricard, had employed a wee bit of… understatement.

The first “mountain” was small. The second was… well, to be blunt, enormous. Our first clue came when the sun rose, and Muxtar pointed to the giant mountain range looming far ahead.

Muxtar: That’s the mountain we need to climb to get to Guinea.

Rose: He’s joking.

Naomi: I don’t know why you think that.

Rose: Ricard said nothing about such a big mountain. Ricard never lies.

Naomi: Oh…. Kay.

On we marched toward the mountain that loomed ever larger with each step.

Muxtar: Actually, we have to climb 3 mountains.

Rose: That’s not true.

Naomi: Why would he lie?

Rose: Why would my taxi driver tell me there were cars to Mali? Everybody lies.

Naomi: So… Right.

It turned out that Muxtar wasn’t telling the truth about there being three mountains to climb.

There were four.

And when he told us later that we’d have to walk a bit farther from the peak to arrive at Mali, that wasn’t true either.

It was two hours of scrambling into and out of dry riverbeds, up steep hills (the kind I thought passed for “mountains” in West Africa, until I was confronted with the real thing), downhill for a moment, and then up even more steep hills.

As Rose began to question whether Mali even existed, I began to argue with Muxtar about the remaining hills.

“We only need to go up, and then down, and then up, and then down, and then up one final time,” he reassured me.

“But you said that half an hour ago, and we’ve already gone up and down twice since then. So this has to be the last hill.” I reasoned, very logically, and not at all petulantly, as if I could argue away the existence of the three hills that remained between us and our destination. It was nearly 10 pm. Muxtar, who was still carrying all our stuff, just smiled patiently, and said, “It’s not far. We’re almost there.”

****

This is an awful lot of whining for what was, in reality, a beautiful hike. We passed through tiny villages, and admired the sunrise (and the sunset). We stopped in one village and offered a man 40 cents for some mangoes from his tree. He started picking, and before we understood what was happening, Muxtar was piling more than twenty mangoes into the already outlandish load he was leading on his bicycle.

We spent a couple hours resting (in a sweaty, sore, heap) in a village at the base of a mountain, where they shared their lunch and their tea, and cheerfully wished us well on the rest of our journey.

And, at first as a distraction against fatigue and the heat, and later because it was so entertaining, (and as a distraction against the exhaustion and pain) Rose and I told each other story after story from our lives and those of our friends.

Rose: Everything you’ve ever heard about boarding school is true…

Naomi: … just as she was about to get deported…

And when we finally arrived in Mali near 10 pm, a mere 18 hours after we’d left Dindafalou, we were tired. We were upset that people had so understated the mountain and the subsequent 10 km. But we weren’t broken.

Yet.

****

Random boy from village: Hello! [Knock, knock, knock] Grand! Hello!

Naomi: HELLOOOOO! [BANG, BANG, BANG.] HEEEEEEELLLLLLLLLOOOOOOO!!??

Rose: There’s nobody there.

Muxtar: There’s nobody there.

Naomi: [BANG. BANG. BANG] HELLLLLOOOOOOOO!!!!!!!

We knew of one hotel in the village of Mali. It was called the Auberge Indigo, and a Peace Corps volunteer we’d met in the village before climbing the last mountain had told us about it.

It’s right by the entrance to the village, she’d assured us.

Of course, she’d also told us that from the peak of the mountain, it’d be an hour’s flat walk to Mali. Everybody lies.

When we finally arrived in the village, we asked for help finding the hotel. 30 minutes of (hilly) walking later, we’d finally arrived at the Auberge. There was a light on inside, but the gate was locked.

Muxtar: There’s nobody there.

Naomi: [BANG. SOB. BANG.] Hello?

Rose: Where else can we stay tonight?

Muxtar: I know a place.

It was a block or so from where we’d been when we arrived and asked for directions to the Auberge. It was also pitch black and deserted.

Rose: And here I was wondering how tonight could get worse.

Muxtar: There’s nobody there.

Rose: Where else can we stay tonight?

Muxtar: I know a place.

We started walking again. It was now after 11 pm.

Rose: All I want is a bed and a place where I can wash off all this sweat.

Naomi: I caution you against getting your hopes up.

And here is where deliverance appeared, in the form of two boys on a motorcycle. They stopped to talk to Muxtar.

Rose: I’m going to ask them for a place to stay.

She meant at their house. Amazingly, however, there was a guesthouse. A weird, almost complete hotel/apartment/villa with tiled, fitted bathrooms, (including large tubs and bidets, in a place with no running water) and built-in light fixtures (in a place with no electricity). There was also a giant, king size bed, with a real, toubab mattress. And while Rose broke down in the bathroom, I settled the details with our well-meaning, but slightly clueless hosts, who wanted to know if we’d be ready to go sightseeing at 7 in the morning, and if maybe we wanted to look at the other rooms before deciding which one to sleep in. (Rose: JUST LEAVE! NOW!)

And we finally settled into bed, hysterically, desperately laughing at our exhaustion, at the employee from the Auberge Indigo who had chased us down right before we found our new hotel, and who wanted us to follow him 45 minutes in the OTHER direction back to his hotel (“But I’m here now! I went out to get some bread! But I’m here!”) and at how much we wished we were back home in Senegal.

But then I stopped laughing. “We can’t just leave here and go back to Senegal tomorrow,” I told Rose. “We have to stay here, and we have to have fun. This trip can’t just be about having an awful time. We’ve come so far to get here. Things have to get better now.”

To be continued…